This past summer, I went to see nine early black-and-white photographs by Nan Goldin on display upstairs at the Gagosian Gallery in London. Downstairs, in the small shop, there were several catalogues for sale that depicted Goldin’s most famous works, such as The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a photobook first published in 1986 that captured the throes of drug addiction, violence, and the complex intimacies of Goldin’s inner circle. There were copies of the exhibition catalogue that accompanied Goldin’s most recent retrospective of filmic work at the Moderna Museet in Stockholm; This Will Not End. I flicked through each, and then through a stand filled with postcards of some of Goldin’s work. Doing so, I found myself drawn to one particular image, one I hadn’t seen before, and decided to buy it. The photo is called Brian’s Birthday, New York City, 1983.

In it is a lone man, his face lit up only by the candles on the birthday cake that has been laid before him. The light from soft flames hits his rugged face, as well as an unopened bottle of champagne and a vase containing three pink roses. We may well think these things romantic, gifts from his lover, perhaps, that have been laid next to a cake. Together they suggest a sweetness, something tender, but this is overpowered by the blackness that surrounds these objects. The dark and the light of the image wouldn’t look out of place in a fresco on the wall of an Italian church lit up by a €1 spotlight, the chiaroscuro leaving the subject swathed in total darkness. Upon first seeing it, I felt sad. I felt, somehow, that there was no one else in that darkness, that this birthday was a lonely one. The space around the man in the photo is void-like, and all-encompassing. It seems hard to imagine that any living thing could be hiding in it, waiting for the candles to be blown out. Yet, of course, there is someone else there; Goldin. She is behind the camera. Perhaps she even bought the cake.

The man is Brian, who was a staple of Goldin’s work from the 1980s. He features heavily in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency as both her lover and abuser, a dual position that allows him to be both the love object and the villain. In one of the most famous photos of Brian, he sits on the edge of the bed whilst Goldin, lying down, admires him. Yet sometimes he is more present when he is absent, such as in Nan one month after being battered, from 1984, which shows Goldin with harsh, dark brown bruises under her eyes, still swollen, yet to fully heal. Seeing this and Laura Poitra’s sublime documentary All The Beauty and the Bloodshed, before seeing ‘Brian’s Birthday, New York City, 1983’, opened up the complicated power of the still image. Removed from context, Brian’s lonely birthday feels sad, almost unbearably so. The sting of past rejections, of isolated Christmases, of not being chosen rises up in the viewer and creates a sense of empathy. In context, however, we may well come to understand that such loneliness is perhaps of Brian's own making, if he has the capacity for such cruelty.

What is really happening in the photo, the exact situation in which it was taken, is, of course, unknown to the viewer. Instead, they create a narrative, bring their own baggage and provide the context to fill the gaps. As Susan Sontag writes in On Photography: ‘Photographs, which cannot themselves explain anything, are inexhaustible invitations to deduction, speculation, and fantasy.’ Different from a painting, the photograph is a record as well as an aesthetic image. Unlike a painting, it is taken in the moment, not built over a period of time through multiple sittings or sketches. The ethical question, then, is how ‘fantasy’ sits alongside truth, how the interpretation of a painting is essentially a reaction to an artist’s rendering while an interpretation of a photo is, in some ways, a distortion of reality.

This torte relationship between fact and fiction is a primary occupation of Irina, the protagonist of Eliza Clark’s debut novel Boy Parts. When we first meet Irina, she is scolded by an older woman for taking sexually suggestive photos of her seventeen-year-old son. Irina shrugs this off as a product of the boy lying rather than any possible failing on her part and she spins the assault at work, one she does not seem overly affected by, into a sabbatical in which she can focus on her art. The break comes at a perfect time, as Irina, a semi-successful (though now somewhat stagnant) photographer, has been asked to collate several works from her back catalogue for a group show in Hackney that focuses on Contemporary Fetish Art.

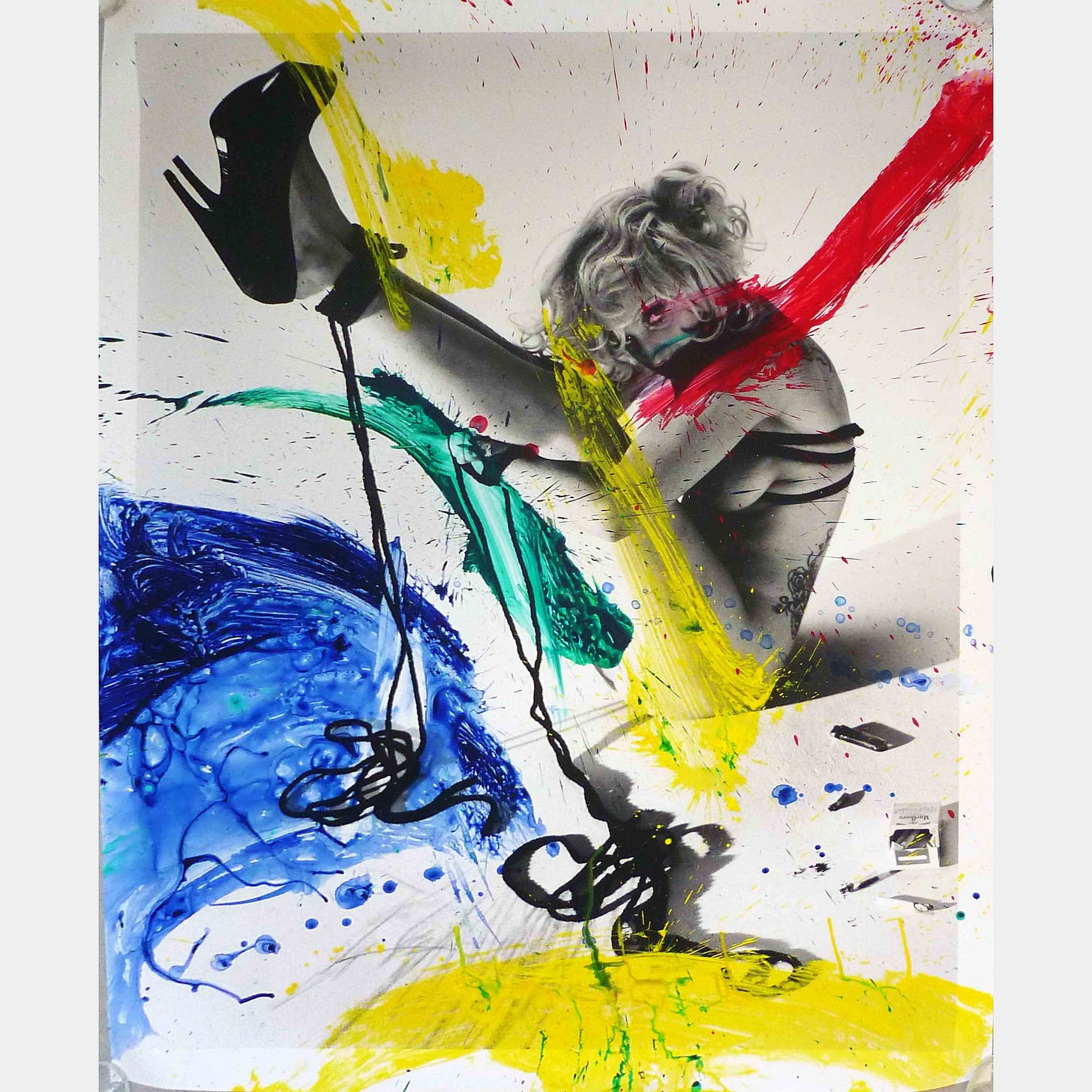

Irina begins to root through her archive of projects that all seem to share a similar theme. They attempt to shock and subvert sexual practice. Many of them have a rather laissez-faire attitude to ethics, embracing instead humiliation as a radical tool in an attempt to balance the status quo. ‘This is my art’, she tells her disapproving tutor at art school regarding a project that includes pithy comments about her fellow students. She believes ‘it’s transgressive’ and makes no apologies about it. As her work progresses, it becomes more focused on the erotic, much to the chagrin of her tutors. In one project, which she called ‘What would you do to be my boyfriend?’, she describes her work as follows:

I spent the summer of 2010 picking up strange men, taking them back to halls, stripping them down to their underwear, and photographing them. I filmed and interviewed while I photographed, and asked them various probing questions about their personal lives, finishing on do you want to be my boyfriend?

Irina, aesthetically, seems to channel artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, Nobuyoshi Araki, and Kat Toronto with her photos capturing sexually liberated practices but, ethically, it seems far more aligned with the works of Marina Abramovic, Ana Mendieta, Yoko Ono, and others whose work attempts to implicate both its subject and its viewer within acts of cruelty. Works that, as Maggie Nelson has it in The Art of Cruelty, ‘deconstruct the tradition of the female body marshaled by the male ringmaster by disappearing the ringmaster, leaving the artists open, sometimes at alarming risk, to whatever might happen next.’

The threat of violence in ‘What would you do to be my boyfriend?’ opens Irina up to more explicit work in which physical acts of harm and sex are forefronted. Unlike Goldin, whose work documents the real ongoing pain of people she knew, Irina’s practice requires the infliction of pain onto men she scouts off the street, with some work being more violent than others. In doing so, she tends to exert her power on shy, slight, feminine men that ‘other people think are ugly, or weird looking.’ A theme of the novel that this work illuminates is how, by and large, female artists are treated far more critically for producing work that, aesthetically at least, shares a connection to pornography—a form that can be quite violent itself. Outside of the work, however, Irina is frequently exposed to violence at the hands of men, some of which have been subjects in her photographs, that sits in contrast to the power she exudes in her work.

If you ask some philosophers, they will tell you that violence cannot exist without power. Famously, Hannah Arendt wrote that violence and power were interconnected ‘politically speaking’ and that ‘it is insufficient to say that power and violence are not the same. Power and violence are opposites; where the one rules absolutely, the other is absent.’ To be a victim of violence is to be powerless, and to enact violence is to wield power. Irina is capable of both. In her work, she enjoys the power she holds, not just as the one who holds the camera, but as the one who is more experienced and sexually confident than her often meek subjects.

Yet, on at least two occasions in Boy Parts, Irina is assaulted by men, one who abuses her while she sleeps and another who, during sex, switches tact and ignores Irina’s requests to stop. After both instances, Irina lashes out. She tries to decide whether to taunt the first man, Will, and considers texting him: ‘Just checking, Will, did you and your useless dick half-heartedly try to rape me last night?’ In the immediate moments after her interaction with John, a suited playboy she meets in a bar who ‘likes it rough’, Irina shatters a champagne flute with the shards cutting into John’s skin, slicing into his eye.

Or does she? On more than one occasion a reader can never be sure if the acts of violence committed by Irina are even real, as all evidence of them seems to fade from view. It’s here we see the effects of the violence that surrounds Irina, both when she wields the power and when she is without it; as a result, her sense of reality continues to unravel. Boy Parts has been compared more than once to Bret Easton Ellis’s lightning-rod of a novel American Psycho in that both Irina and Patrick Batemen are two unreliable narrators who don’t seem to be able to get a handle on the truth. For Irina, it all seems linked to a traumatic experience with a model, in a situation that Irina is never able to totally prove happened. The previous violent incident haunts her and sends her further into erratic, reckless, and brutal behaviour. The novel, then, reckons with internal effects of violence, and that, as a subject, is something Clark seems perpetually interested in.

On the face of it, Penance, Clark’s second novel, may seem like a vastly different book than Boy Parts. Stylistically, the former is a metafictional satire about the True Crime industry, while the latter is an increasingly unhinged monologue from a woman who is slowly losing her grip on reality. Yet, thematically, both books are obsessed with the inner workings of those who commit violence. In Penance, however, we meet the violence in a detached way, with the cold facts of a murder case. In the first few pages, we learn that three high-school-aged girls have killed another by burning her alive in a beach chalet. The victim, Joni Wilson, survived long enough to name her attackers to the police. They are Dolly, Violet, and Anjelica. The next 400 pages, then, set out the ways in which their lives intertwined with Joni’s, how certain events brought them together, and how a growing obsession in the occult drew them to kill her in such a dark, violent way in their working-class beach town on the Yorkshire coast.

What sets it apart from her first novel is that Penance works on the conceit that it was not written by Clark but, as the short note on the first page tells us, by Alec Z. Carelli, a disgraced tabloid journalist who has written a number of semi-successful True Crime books but, most recently, has released a few unsuccessful ones. In the wake of his latest failure, Carelli sets up in Crowe-on-Sea, a fictional town that lies between Scarborough and Whitby. He is there to write the definitive book on Joni’s murder, a book that will allow her family to find peace and will act as a guide to those who are increasingly drawn to the case due to its sudden popularity in the True Crime space. To do so, he seeks out witnesses, hounding the families of those involved until they agree to talk to him. He acquires ‘therapeutic writing’ from the facilities where the girls were held after they were convicted, extracts that discuss their experiences and the period leading up to the murder.

We also learn in that short introductory note, however, that in the world of the novel, Penance was pulled from shelves shortly after its original publication due to accusations of illegality and ‘misrepresenting and even fabricating some of the content’ in its interviews. As such, we can never trust the information put forward by Carelli, much like we come to not trust Irina, and we can never be sure that anything we are reading is true. We only get his assessment of events, his version of how the four girls at the centre of the book come across, and so where Boy Parts placed us inside Irina’s head as accomplices to violence she enacted and witnesses to that done against her, Penance takes a different tact by placing the violence at a distance. The crime happened years ago, on the night of the Brexit referendum in 2016, and all we have is the reports, the detailed eye-witness statements, and the power of our imagination. While the first few pages contain gruesome, up to the minute detail of what happened to Joni, the rest of the book is relatively free from violence. Instead, Penance very much asks us why we are interested at all.

This is the same question asked of those who consume the genre that Clark aims to critique: True Crime. Why? What is it about the blood and guts, the terror and fear, the idea of humanity at its most evil that draws you in to listen while you drive to work, clean out your wardrobe, or walk the dog? It is, perhaps, the very same impulse that has driven us to the morbid for centuries. While True Crime as we know it may appear relatively new, the genre has its roots in 17th Century piety with priests writing pamphlets based on the confessions of vicious criminals held in British prisons. They were produced and sold for the ‘official’ reason that they would save the moral soul of the country by discouraging readers from committing violent acts, but of course this is not how they were consumed. As the years progressed, such stories were turned into plays for the masses, into cheaply produced books and magazines until, within the last decade, they have become podcasts, documentaries, and eight-hour television dramas depicting some of the worst crimes imaginable.

In her book Regarding the Pain of Others, the act of looking at or considering violent images concerns Sontag. ‘There is shame as well as shock in looking at the close-up of a real horror’, she writes. ‘Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it […] or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be.’ Sontag is writing, mostly, about images of war, and it’s unclear exactly how she would feel about the proliferation of content that sells itself on violence (other than to say she likely wouldn’t be impressed). But there is, perhaps, a base desire to see such things. Sontag writes:

Everyone knows that what slows down highway traffic going past a horrendous car crash is not only curiosity. […] It is also, for many, the wish to see something gruesome. Calling such wishes "morbid" suggests a rare aberration, but the attraction to such sights is not rare, and is a perennial source of inner torment.

Exactly what such things do for us is up for debate. Sontag suggests that ‘images of the atrocious can answer to several different needs’ such as ‘To steel oneself against weakness. To make oneself more numb. To acknowledge the existence of the incorrigible.’ This is often the same argument lobbied by True Crime fans, that an exposure to violence leads to an awareness. There is no doubt that the victims in such documentaries are so often women and the main consumers of the genre are women too. It may be that there is a catharsis in knowing the brutal details of how the world so often operates and True Crime can act as a vehicle for processing a culture that is vehemantly violent toward women.

Penance doesn’t really take aim at those who consume True Crime, but rather those who make it, at those who turn tragedy into entertainment. Carelli, more than once, uses his own trauma as a means of gaining trust, a trust we know from the opening ‘Publishers Note’ he will betray. We feel, often, that his tactics for gaining interviews can be problematic. In one interview with Dolly’s half-sister, the only member of Dolly’s family willing to meet with him, we sense a line being crossed. ‘You’re a creep,’ she tells him at the end of their interview, after he has questioned her take on events. ‘And I want you to put that into your nasty little book.’

The ethics of True Crime and how it capitalises on a violent culture by sensationalising traumatic events into ‘must-see’ television is a tricky knot to untangle. On the one hand, it can be argued that it is simply supply and demand. There is an appetite for it and someone might as well be the one to offer it up. Yet, as someone who has no interest in the genre, I find it hard to understand its virtues, and, more than once, I have asked friends what they find so appealing about it. More so, I am often concerned about the commercialisation of violence, real violence, and people that turn the darkest time in other people’s lives into salacious content.

Many times, whilst reading Penance, I was reminded of a scene in Maggie Nelson’s memoir The Red Parts. In her previous book, Jane: A Murder, Nelson reckoned with the violent murder of her aunt, Jane in 1969 and, in The Red Parts, she is once again confronted by that crime as the case is reopened based on new evidence. At one point, she describes being approached by the producers of a show called 48 Hour Mystery who want to use the story of her aunt’s murder for an episode. Nelson goes back and forth on whether to take part in a show she is fairly certain they will make with or without her, and is told the show aims to help ‘other people mourn.’ Nelson asks ‘if there is a reason why stories about bizzare, violent deaths of young, good-looking, middle-to upper-class white girls help people mourn better than other stories’ and is met with no response.

For Clark, violence as a form of cultural and commercial capital is an interesting subject. In one podcast interview she addresses exactly why violence plays a central role in her fiction:

Extreme acts of violence are something that happen every day on planet earth and I think, particularly in the kind of global north, we’re very isolated from the very day-to-day happenings of warfare and violence and death. The sort of things that do happen are sort of presented as out of the ordinary when that’s not necessarily the case. Yeah, I just see violence as, like, a thing that exists so why should it be something that we avoid in storytelling when it is so present in day-to-day life?

Perhaps it’s true that such depictions of violence feel so shocking because we have become adept at avoiding them. How easy it can be to panic at violence on our own streets when we are numb to the ongoing daily violence in other parts of the world. Yet, exactly what effect being exposed to the violence we try to ignore has is still up for debate. As Sontag writes, ‘Compassion is an unstable emotion. It needs to be translated into action, or it withers.’

Clark’s work, however, shifts that needle. It asks us not only to bear witness to violence, but to see it in context with the work itself being an act of compassion turned into action. In her upcoming collection of short stories, She’s Always Hungry, the titular story begins with violence between men and teases out the question of what place such violence would have under a matriarchy rather than any kind of political system we live under. Other stories, too, engage with acts of violence that never intend simply to shock. After finishing any of Clark’s three books, a reader is unable to walk away without feeling a sense of complicity, without a niggling feeling that such violence is brought around by unequal systems, by capitalism, by unfair government policies, by an ever starved appetite that needs to be fed.

It is perhaps here that we see exactly why depictions of real violence sit so uneasily. It may even be considered simple: we do nothing about it. The proliferation of True Crime has done nothing to make the world safer. The onslaught of violent images from countries at war have done very little to bring about peace. Instead, we melt into a kind of numbness. Clark’s fiction doesn’t allow for such numbness, much in the way Goldin’s photos do not. Instead, her work writhes with sensitivity, with questions, and with an overwhelming feeling that violence cannot only exist in art as a means of entertainment; instead, it needs to be viewed as the complex social problem it is.

You can pick up Boy Parts and Penance (Faber & Faber) from your local independent bookshop such as The West Kirby Bookshop (West Kirby), News From Nowhere (Liverpool), Queer Lit (Manchester) or you can order copies via Hive.co.uk

She’s Always Hungry is out on 5th November 2024 and is available for pre-order from any of the above.